Sexual Trauma, Symptoms, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among the Asexual Adult Population: An Analysis of the 2017 Ace Community Census

cw: discussion of sexual trauma, PTSD, and sexual violence

Abstract

The objective of this study was to quantify the prevalence of sexual trauma and its respective types, and symptoms and receipt of PTSD diagnosis among asexual individuals in an online, asexual community.

A secondary data analysis was conducted among adult asexuals from the 2017 Ace Community Census (n = 5,440). Sexual trauma prevalence, as well as symptoms of and the receipt of PTSD diagnosis were determined. Inferential statistics were used to compare and contrast sexual trauma victims and non-victims.

The prevalence of sexual trauma victims among asexual adults was 46.1%. Most victims kept remembering the event even though they did not want to (60.1%) and had distressing memories of the event (62.3%). Non-gender identifying asexuals were most likely to be victims (45.8%) and report a PTSD diagnosis (11.8%). PTSD prevalence was 8.6% (n=216/2,509) among sexual trauma victims.

Sexual and mental trauma, including PTSD, are legitimate issues among asexual individuals. Improved dialogue and trust between healthcare providers and the asexual population is critical for early identification and treatment.

Asexual awareness and education for healthcare providers will improve treatment of asexual patients.

Key Words: asexual, post-traumatic stress disorder, sexual trauma, healthcare

Introduction

Asexuality is generally defined as lack of sexual attraction to either sex, or simply stated, anyone (Bogaert, 2004; Decker, 2015; Yule, Brotto, & Gorzalka, 2015). The Asexuality and Visibility Education Network (AVEN), an online community for self-identified asexuals, states “Many asexual people may experience forms of attraction that can be romantic, aesthetic, or sensual in nature but do not lead to a need to act out on that attraction sexually. Instead, we may get fulfillment from relationships without sex, but based on other types of attraction” (AVEN 2019). As definitions of asexuality vary (Jones and Hayter 2017), so, too, does the estimated prevalence of asexuals, ranging from 1.05%1 to 0.3% of men and 0.5% of women in the United Kingdom (Aicken, Mercer, and Cassell 2013). While sexual trauma has garnered increased attention and investigation, particularly among female victims, little is known about asexual victims and subsequent sequelae, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Asexuals often face misconceptions about their orientation, which may put them at risk of their health issues being ignored or misunderstood and increase their risk of sexual trauma. Since asexuals may face similar social stigma to that experienced by homosexual and bisexual individuals, in that they may also experience discrimination and/or marginalization, it is possible that asexual individuals might also experience higher rates of psychiatric disturbance compared to those who are considered sexual (Yule, Brotto, and Gorzalka 2013). Asexuals may experience additional stigma because of the experience of a lack of sexual attraction in a culture that is arguably dominated by sexuality (Yule, Brotto, and Gorzalka 2013).

Sexual minority groups, usually referring to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, may face barriers in accessing appropriate healthcare (Jones and Hayter 2017; Dahl, Fylkesnes, Sorlie, and Malterud 2012; Davy and Siriwardena 2012; Shields, Zappia, Blackwood, Watkins, Wardrop, and Chapman 2012). Communication between healthcare providers and their patients is paramount to achieve optimal treatment (Jones and Hayter 2017). Improved understanding of sexual trauma history and mental health, including PTSD among asexual patients is necessary not only for their general health and well-being, but to enhance the efforts to recognize the existence of the asexual identity. The associations between sexual trauma and PTSD among asexuals are not well-studied. The one published study (Parent and Ferriter 2018) found that asexuals were more likely to report a receipt of diagnosis of PTSD and sexual trauma within the past twelve months, compared to non-asexuals. However, the focus of this research was limited to college students within the United States and included a relatively small number of asexuals (n=228).

Asexuals may be more likely than non-asexuals to recognize sexual aggression as sexual assault (MacNeela and Murphy 2015). This potentially heightened awareness emphasizes post-trauma communication with others, including healthcare providers and law enforcement, to treat the subsequent trauma and apprehend the perpetrator(s). There are complexities in assessing types of sexual experiences by self-report for reasons including, but not limited to, inconsistent definitions of “consent” and the relationship between verbal coercion and consent (Pugh and Becker 2018). Sexual violence is a concept not easily measured, primarily due to inconsistent definitions of sexual assault and rape; differing reporting requirements across local, state, and national law enforcement; and low conviction rates (National Crime Week Victims’ Guide 2018).

In this research study, rather than use the term of “assault”, “trauma” was used and reported by each type. The purpose of this research was to quantify and analyze the prevalence of sexual trauma and its respective types, and symptoms and receipt of diagnosis of PTSD among asexuals in an online, asexual community.

Methods

A secondary data analysis of the 2017 Ace Community Census was conducted, with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from the University of Toledo. Ace is a shorthand term for asexual. The 2017 Census was an online survey that contained 107 questions. It is an annual research project completed by the AVEN Survey Team. In addition to demographic variables including age, education, country, race, and ethnicity, the survey contained questions regarding orientation, asexual identity, relationships, sexual history, sexual violence, libido, sexual attitudes, suicide, negative experiences, asexual communities, offline LGBTQ spaces, and personal perspectives (AVEN Ace Community Census 2017).

The Census represents a convenience sample recruited via snowballing sampling techniques. Announcements containing a link to the survey were posted on several major asexual websites including but not limited to the Asexual Visibility Education Network and The Asexual Agenda, as well as in asexuality-themed groups on various popular social networking sites, including but not limited to Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, Reddit, and Livejournal (AVEN Guide to the Asexual Community Survey Data 2017). Respondents were encouraged to share the link with any other asexual communities or individuals they knew. Although recruitment was focused on asexual spectrum respondents, non-asexual respondents who encountered the survey were also encouraged to complete it.

The survey consists of a core set of questions that are repeated each year, and selected topical questions. Each year, the survey is revised, determining what sections to rotate in or out and finding ways to improve questions. Since the Ace Community Census is not affiliated with any university or formal research organization, there was no formal IRB approval process. However, the instructions on the first page of the Census state, “All data collected will be kept confidential, and no identifying information will be collected. Please note that some data may be shared with other researchers at qualifying research institutions who request information from the survey team for academic purposes. Taking part in this survey is completely voluntary and you can stop the survey at any time. Most questions in the survey are completely optional, and can be left blank if you are uncomfortable or do not know how to answer” (AVEN Ace Community Census 2017).

Additional instructions on the first page discuss the sensitive topics covered in the survey and that if someone does not wish to participate in the survey, they may use the back button in their browser to exit this page. Further resources (phone numbers and websites) including those for the National Sexual Assault Hotline, Veterans Crisis Line, FORGE Transgender Sexual Violence Project are provided within the survey following the sexual trauma questions.

Asexual Identity

Asexual identity was obtained through the question, “Which of the following labels do you most closely identify with?” followed by the options of asexual, gray-asexual, demisexual, questioning if asexual/gray-asexual/demisexual, or none of the above. For this study, only those who identified as “asexual” and were eighteen years of age or older were included (n = 5,440).

Sexual Trauma, Symptoms, and PTSD

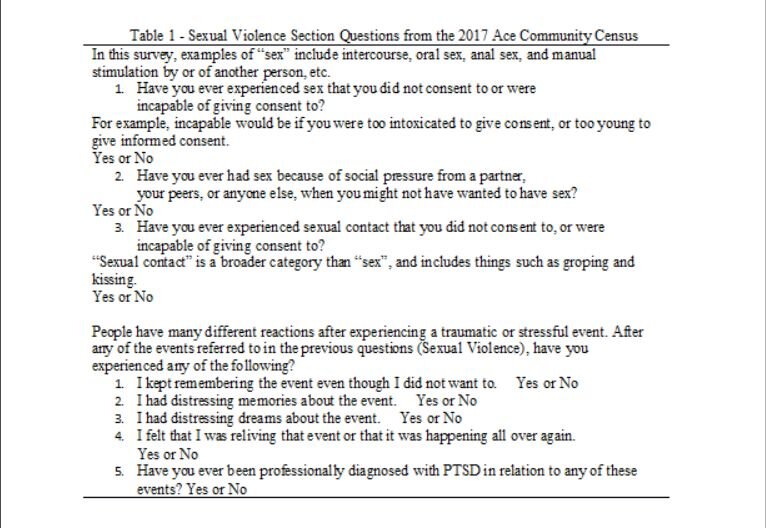

The Sexual Violence section of the survey included three questions pertaining to sexual trauma, four questions related to symptoms following the trauma, and a question asking respondents to indicate if they had been professionally diagnosed with PTSD (Table 1). Respondents were directed to skip the symptoms and PTSD questions if they answered “No” to all three of the sexual trauma questions.

The three sexual trauma questions were analyzed separately, as each pertains to a specific type of violence (rape, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual contact). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) defines “rape” as “any completed or attempted unwanted vaginal (for women), oral, or anal penetration through the use of physical force (such as being pinned or held down, or by the use of violence) or threats to physically harm and includes times when the victim was drunk, high, drugged, or passed out and unable to consent.” (NISVS Data Brief 2015). This aligns with the question in Table 1, “Have you ever experienced sex that you did not consent to or were incapable of giving consent to?”

The second sexual trauma question, “Have you ever had sex because of social pressure from a partner, your peers, or anyone else, when you might not have wanted to have sex?”, aligns with the NISVS definition of “coercion”. “Coercion” is “unwanted sexual penetration that occurs after a person is pressured in a non-physical way”, including “unwanted vaginal, oral, or anal sex after being pressured in ways that included being worn down by someone who repeatedly asked for sex or showed they were unhappy; feeling pressured by being lied to, being told promises that were untrue, having someone threaten to end a relationship or spread rumors; and sexual pressure due to someone using their influence or authority.” (NISVS Data Brief 2015).

The third sexual trauma question, “Have you ever experienced sexual contact that you did not consent to, or were incapable of giving consent to?”, aligns with the NISVS definition of “unwanted sexual contact”, defined as “unwanted sexual experiences involving touch but not sexual penetration, such as being kissed in a sexual way, or having sexual body parts fondled, groped, or grabbed.” (NISVS Data Brief 2015).

Gender Identity

Gender information was obtained through the question, “Which of the following best describes your gender identity?”, followed by the options of “Man or male, Woman or Female, and None of the above”. Those who indicated “None of the above” could be transgender, gender-neutral or agender, non-binary, or another designation. However, there was a separate question in the Census, “Do you consider yourself trans?”, followed by the options of “Yes, No, and Questioning or Unsure”.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the prevalence and distribution of the three types of sexual trauma, symptoms, and receipt of PTSD diagnosis. An independent samples t-test was used to compare the mean age of those who had ever been a victim of sexual trauma to those who had not. Chi-square analyses were used to compare demographics between sexual trauma victims and non-victims, as well as the proportions of asexuals by gender for each of the three sexual trauma types, symptoms, and PTSD diagnosis. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used for the data analysis.

Results

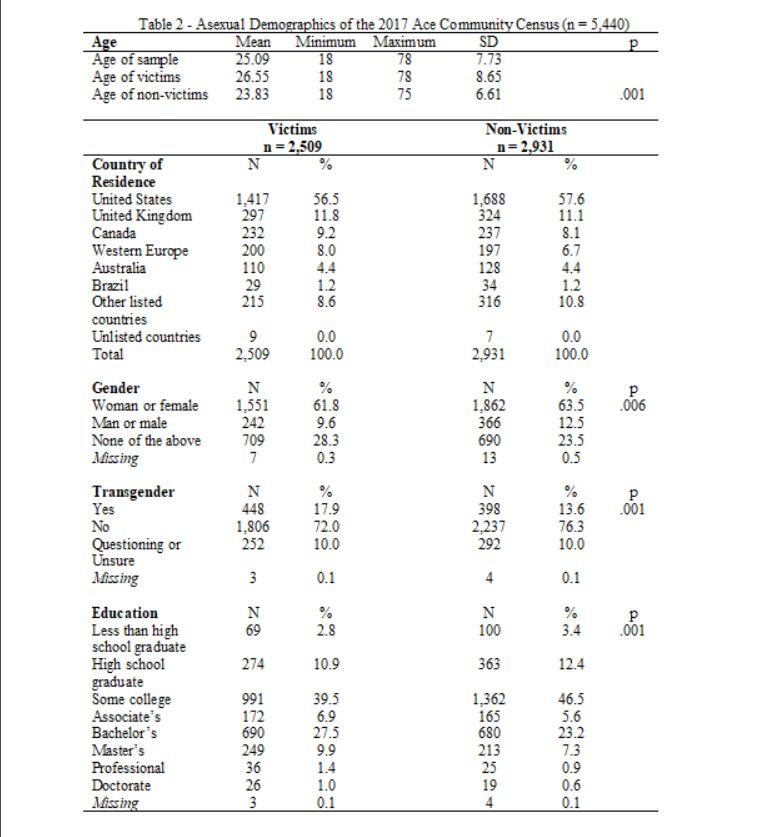

Among this online community of asexuals, 3,413 identified as woman or female, with 74 (2.2%) also identifying as transgender; 1,399 did not identify with a gender, with 608 also identifying as transgender (43.4%); 608 identified as man or male, with 161 also identifying as transgender (26.4%); and twenty did not answer (chi-square = 22.09, df = 2, p = 0.006). (Table 2). In total, asexuals from eighty-nine different countries completed the 2017 Ace Community Census. The top three countries of residence were the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada (Table 2).

Sexual Trauma

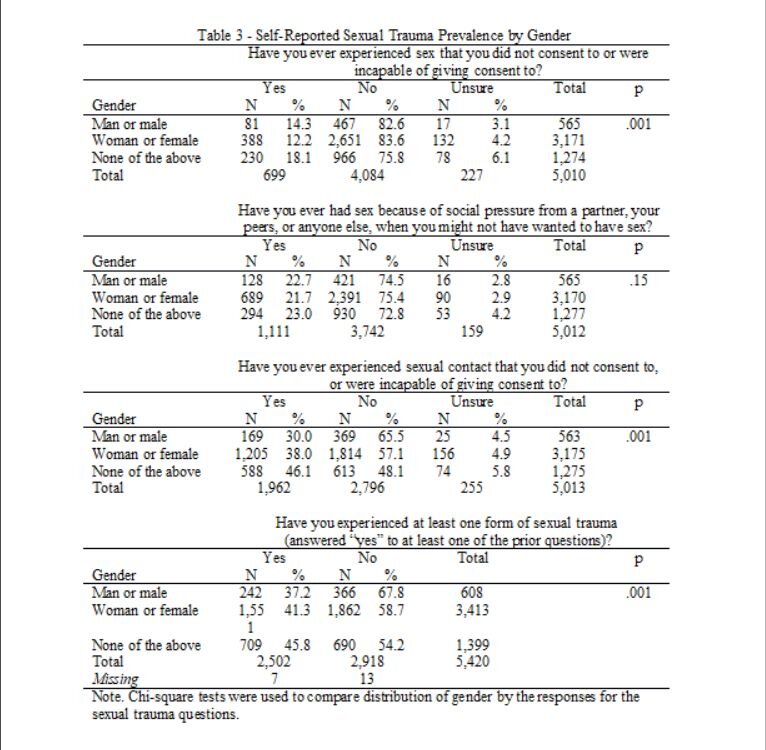

Among those who had ever been a sexual trauma victim, there was a statistically significant difference in age between victims (mean = 26.55) and non-victims (mean = 23.83) (t = 13.16, df = 5,438, p = .001) (Table 2). Though females were the most prevalent gender (n = 1,551) to self-report as sexual trauma victims, non-gender identified individuals were most likely, by proportion, to be sexual trauma victims (45.8%) (chi-square = 22.09, df = 2, p < .01) (Table 3).

Types of Sexual Trauma

Non-gender identified individuals were most likely to have experienced all types of sexual trauma (Table 3). This includes experiencing sex that they did not consent to, or were incapable of giving consent to (42.8%) (chi-square = 39.92, df = 4, p = .001), sex because of social pressure from a partner, peers, or anyone else when they might not have wanted to have sex (23.0%) (chi-square = 6.74, df = 4, p =0.15), and experiencing sexual contact that they did not consent to or were incapable to consent to (46.1%) (chi-square = 55.14, df = 4, p = .001).

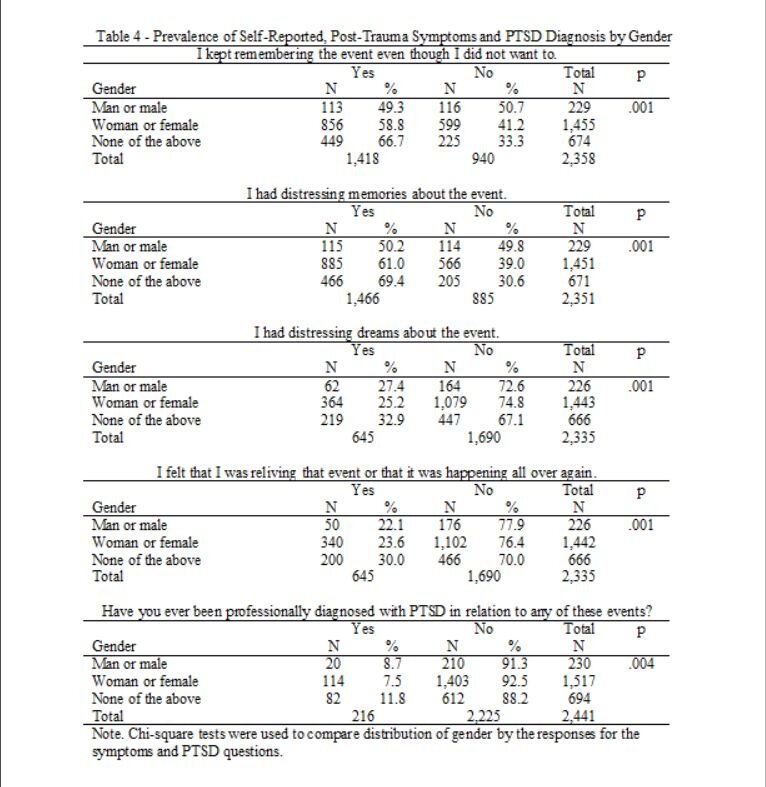

PTSD and Symptoms

There were 216 (114 females, 20 males, and 82 non-gender identified) sexual trauma victims who reported receipt of a PTSD diagnosis (chi-square = 39.29, df = 2, p = .001) (Table 4). Non-gender identified, asexual victims were statistically most likely to report symptoms (chi-square range = 11.36 to 29.90, df = 2, p = .001) and receipt of a PTSD diagnosis (chi-square = 10.93, df = 2, p = .001) (Table 4). A proportion did not answer the symptom questions or the PTSD diagnosis question, resulting in a potential underestimation of the prevalence. Further, everyone who completed the survey chose to skip the two questions pertaining to suicide.

The majority of victims of any type of sexual trauma, among all gender identities, kept remembering the event even though they did not want to and had distressing memories about the event (Table 4). Those who did not identify with a gender had the greatest proportion of victims who reported suffering these two symptoms (66.7% and 69.4%), followed by females (58.8% and 61.0%), and males (49.3% and 50.2%), respectively. Similarly, those who did not identify with a gender had the greatest proportion of victims who had distressing dreams about the event (32.9%) and felt they were reliving that event or that it was happening all over again (30.0%).

Discussion

In this study, we found asexuals were victims of various sexual trauma types and suffer symptoms affecting their mental health, including the receipt of PTSD diagnosis. Specifically, non-gender-identified, asexual adults were most likely to be victims of all sexual trauma types and most likely to report symptoms and a PTSD diagnosis.

The proportion of females who reported experiencing sex that they did not consent to or were unable to consent to (12.2%) is lower than the lifetime risk of 20.0% experiencing completed or attempted rape; but more commonly reported among males (14.3%) (Table 2) than the male lifetime risk of 7.1% made to penetrate someone (complete or attempted) reported by the NISVS (NISVS Data Brief 2015). Asexuals may report that they are sometimes pressured to date or have sexual contact because others perceive their lack of interest as suggesting they have not found the right person yet or need to have a good sexual experience (Decker 2015; Bianchi 2018). Cultural norms around male interest in sex may help explain why more males in this study reported non-consensual sex compared to the NISVS (Bianchi 2018).

Approximately twenty-two percent of each gender identity reported ever having sex because of social pressure from a partner, peer, or anyone else, when they might not have wanted to have sex (coercion). This is slightly higher than the lifetime risk of 16% of women experiencing sexual coercion (NISVS Data Brief 2015).

Non-gender identifying, asexuals, were the most likely to report having been a victim of sexual trauma (45.8%) than females (41.3%). Non-gender identifying trauma victims were also most likely to report non-consensual sexual contact, ahead of female victims. However, the lifetime risk of reporting unwanted sexual contact among all women is 37.0% (NISVS Data Brief 2015), similar to the 38.0% found among asexual female victims in this study.

In a study of sexual victimization and subsequent police reporting by gender identity among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adults, transgender individuals reported having experienced sexual assault and rape more than twice as frequently as cisgender LGBQ individuals (Langender-Magruder, Walls, Kattari, Whitfield, and Ramos 2016). Similarly, the 2015 United States Transgender Survey, which was completed by 27,715 individuals (of whom 10% identified as “asexual”), indicated that 10% of transgender individuals were sexually assaulted in the year prior to completing the survey and 47% were sexually assaulted at some point in their lifetime (Report of the U.S. Transgender Survey 2015).

The prevalence of sexual trauma victims, their symptoms, and PTSD is a call to action for healthcare providers and public health professionals. Further, more research is needed to determine why non-gender identified individuals may have a higher risk of trauma, symptoms, and PTSD, compared to other genders. Among asexuals in this study, 8.6% (216 out of 2,509) of sexual trauma victims self-reported a receipt of a PTSD diagnosis. This proportion is greater than the 3.5% (8 out of 228) of asexuals who were sexual assault victims that self-reported a PTSD diagnosis (Parent and Ferriter 2018). The gender-specific prevalence of self-reported PTSD diagnosis is greater than that reported in the 2007 National Comorbidity Survey (5.2% for adult females and 1.8% for adult males) (Harvard Medical School 2007). However, these figures are based on the entire sample, not restricted to sexual trauma victims. In this study, 4.0% (216 out of 5,440) of asexuals self-reported a PTSD diagnosis, nearly identical to the 3.6% past-year prevalence of PTSD among adults (Harvard Medical School 2007).

It has been suggested that asexual identity may facilitate greater exploration and self-reflection and potentially lead to recognition that prior sexual experiences were assault (MacNeela and Murphy 2015). Others have posited that for some individuals who identify as asexual, a history of sexual trauma may influence their identification as asexual (Parent and Ferriter 2018; Leiblum and Wiegel 2002; Rosen 2000). The suggestion is victims may intentionally adopt an asexual identity to avoid discussing their sexual trauma history and/or avoid sexual behavior due to prior sexual trauma (Parent and Ferriter 2018; Leiblum and Wiegel 2002; Rosen 2000). While this may be a possibility for some, it is a problematic hypothesis.

Though sexual trauma may be associated with aversion to sexual behavior (Leiblum and Wiegel 2002; Rosen 2000), suggesting that asexual orientation is the result of a prior trauma can further contribute to the misconception that asexuals are simply sex-repulsed or sex-avoidant, implying that asexuality is more of a behavior rather than an orientation. Common themes of the coming out process for asexual individuals include skepticism from family and friends, lack of acceptance and misunderstanding, and non-disclosure of asexual identity (Robbins, Low, and Query 2016). The aforementioned speculation only perpetuates these themes for asexuals.

Though the data were provided by an online survey, the age of participants ranged from 18 to 78 years. This diverse age range reflects not only the varied ages of the asexual population, as they age just like everyone else, but that asexuals of all ages go online and interact with others in the asexual community. Additionally, there is no source of data that approaches the sample size of self-identifying asexuals provided by the 2017 Ace Community Census - completed by 5,440 adults from eighty-nine countries around the world.

There is a need for education and awareness to providers and the public regarding the asexual orientation. This will foster a trusting environment where patient-provider communication can be completely open and honest and free from judgement and disdain. The needs for asexuals to access and obtain quality healthcare are no different than anyone else.

Trust between patient and healthcare provider is essential. There are individuals whose asexuality is still dismissed by healthcare providers (Foster and Scherrer 2014). Thus, sexual trauma and the mental anguish that results from it may be ignored and thus, not disclosed by the patient, delaying treatment and impairing their health and well-being. Like any other health issue, the earlier it can be identified and treated, the better the prognosis for the patient. Asexuals are no different from anyone else in this regard.

The purpose of this study was descriptive in nature, to determine the prevalence of sexual trauma and its respective types, and symptoms and receipt of a PTSD diagnosis among asexuals from an online community. Future research endeavors should seek information regarding symptoms and PTSD diagnosis among those who do not report as victims of sexual trauma. One method for accomplishing this objective would be to include these questions, and perhaps others, for all respondents of the Ace Community Census, stating that PTSD can result from a multitude of factors, in addition to or instead of sexual trauma. This would allow for comparison between sexual trauma victims and non-victims, and among various orientations.

Limitations

Snowball sampling is a useful choice of sampling strategy when the potential study population is hard-to-reach, such as asexuals. However, since snowball sampling does not select units for inclusion in the sample based on random selection, unlike probability sampling techniques, it is impossible to determine the possible sampling error and makes statistical inference testing difficult (Crossman 2019). The data is not population-based, but rather from an online, asexual community. Therefore, the sample may not be representative of the asexual population.

These data relied on self-report of receiving a PTSD diagnosis. Though the specific verbiage preceding the symptoms and PTSD questions was “After any of these events referred to in the previous questions (sexual violence), have you experienced any of the following”, and “professionally diagnosed with PTSD in relation to any of these events”, there is no way of definitively knowing if prior sexual trauma contributed to the diagnosis of PTSD nor if the diagnosis occurred before or after the sexual trauma.

Those with symptoms may not recognize them as such and, therefore, may not see a healthcare provider. It is possible participants may have been diagnosed with PTSD but not had the diagnosis communicated to them, they may misremember diagnoses, and may rely on Internet tests of questionable validity to self-diagnose. Access to medical records to determine if a physician diagnosis of PTSD was made would be the best method to validate PTSD numbers. It was not possible to detect the reason(s) for the onset of PTSD. Future research may use the Life Events Checklist (Gray, Litz, Hsu, Lombardo 2004) to separate individuals with sexual trauma history from those who may have PTSD arising from other events.

Those who experienced sexual trauma, especially from an intimate partner, may not label it as such. Thus, histories of sexual trauma are limited by wording and content of the questions and make one speculate if the three questions in the 2017 Ace Community Census were able to capture the full range of sexual trauma and its manifestations, and not refer to the same behavior across different questions. Though the three questions appear to align with the NISVS definitions, there was no indication they were used to help draft the questions (AVEN Guide to the Asexual Community Survey Data 2017). More questions on this topic may be necessary in future studies.

The sexual trauma could have occurred at any time, as the questions did not pertain to a specific time period. Further, we do not know if victims had been sexually traumatized more than once in their lives. Reaching a consensus on defining and evaluating issues such as verbal sexual coercion and consent, which are important aspects to sexual trauma, will help researchers better understand these issues and suggest methods for sexual trauma prevention (Pugh and Becker 2018).

Public Health Implications

These findings indicate that asexuals are not only victims of sexual trauma, but also the resultant mental anguish and suffering. The asexual population is still trying to gain acceptance not only in the LGBTQ+ population, but with healthcare providers and the general public. Asexuals need to be empowered to seek medical care, as well as law enforcement assistance, in the event they have been assaulted. Asexual education and awareness for healthcare providers could help asexual individual to be more willing to seek care, increase patient-provider dialogue, and improve the treatment of asexual patients.

References

Aicken, C.R.H., C.H. Mercer, and J.A. Cassell. 2013. Who Reports Absence of Sexual Attraction in Britain? Evidence from National Probability Surveys. Psychology and Sexuality 4 (2): 121–135. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774161

AVEN (Asexuality and Visibility Education Network). Overview. https://asexuality.org/?q=overview.html. Accessed August 10, 2019.

AVEN (Asexuality and Visibility Education Network) Survey Team. 2017 Ace Community Census. https://asexualcensus.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/2017rawtext.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2019.

AVEN (Asexuality and Visibility Education Network) Survey Team. Guide to the Asexual Community Survey Data. https://asexualcensus.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/dataguide.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2019.

Bianchi, Tori. 2018. Gender Discrepancy in Asexual Identity: The Effect of Hegemonic Gender Norms on Asexual Identification. PhD diss., Western Washington University.

Bogaert, A.F. 2004. Asexuality: Prevalence and Associated Factors in a National Probability Sample. Journal of Sex Research 41 (3): 279-287.

Crossman, A. What is a snowball sample in sociology? https://www.thoughtco.com/snowball-sampling-3026730. Updated May 6, 2019. Accessed August 10, 2019.

Dahl, B., A.M. Fylkesnes, V. Sorlie, and K. Malterud. 2012. Lesbian Women’s Experiences With Healthcare Providers in the Birthing Context: A Meta-ethnography. Midwifery 29 (6): 674-681. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.008

Davy, Z., and A.N. Siriwardena. 2012. To Be or Not to be LGBT in Primary Care: Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People. The British Journal of General Practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 62 (602): 491-492. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X654731

Decker, J.S. 2015. The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality. New York: Skyhorse Publishing.

Foster, A.B., and K.S. Scherrer. 2014. Asexual-identified Clients in Clinical Settings: Implications for Culturally Competent Practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 1 (4): 422-430. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000058

Gray, M.J., B.T. Litz, J.L. Hsu, and T.W. Lombardo. 2004. Psychometric Properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment 11 (4): 330-341.

Harvard Medical School. National Comorbidity Survey. https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/table_ncsr_12monthprevgenderxage.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2019.

Jones, C., and M. Hayter. 2017. Understanding Asexual Identity as a Means to Facilitate Culturally Competent Care: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26 (23-24): 3811-3831. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13862

Langender-Magruder, L., N.E. Walls, S.K. Kattari, D.L. Whitfield, and D. Ramos. 2016. Sexual Victimization and Subsequent Police Reporting by Gender Identity Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Adults. Violence and Victims 31 (2): 320-331. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708

Leiblum, S.R., and M. Wiegel. 2002. Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Treating Female Sexual Dysfunction. World Journal of Urology 20 (2):127-136.

MacNeela, P., and A. Murphy. 2015. Freedom, Invisibility, and Community: A Qualitative Study of Self-identification With Asexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior 44 (3): 799-812. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0458-0

NISVS (National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey): 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2019.

Parent, M.C., and K.P. Ferriter. 2018. The Co-occurrence of Asexuality and Self-reported Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis and Sexual Trauma Within the Past 12 Months Among U.S. College Students. Archives of Sexual Behavior 47 (4): 1277-1282. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1171-1

Pugh, B., and B. Becker. 2018. Exploring Definitions and Prevalence of Verbal Sexual Coercion and its Relationship to Consent to Unwanted Sex: Implications for Affirmative Consent Standards on College Campuses. Behavioral Sciences. 8 (8): 1-28. doi: 10.3390/bs8080069

Robbins, N.K., K.G. Low, and A.N. Query. 2016. A Qualitative Exploration of the “Coming Out” Process for Asexual Individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior 45 (3): 751-760. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0561-x

Rosen, R.C. 2000. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Sexual Dysfunction in Men and Women. Current Psychiatry Reports 2 (3): 189-195.

Shields, L., T. Zappia, D. Blackwood, R. Watkins, J. Wardrop, and R. Chapman. 2012. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Parents Seeking Healthcare for Their Children: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 9 (4): 200-209. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2012.00251.x

The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed September 26, 2019.

Yule, M.A., L.A. Brotto, and B.B. Gorzalka. 2015. A Validated Measure of No Sexual Attraction: The Asexual Identification Scale. Psychological Assessment 27 (1): 148-160. doi: 10.1037/a0038196

Yule, M.A., L.A. Brotto, and B.B. Gorzalka. 2013. Mental Health and Interpersonal Functioning in Self-identified Asexual Men and Women. Psychological Assessment 4: 136-151. doi: 0.1080/19419899.2013.774162

2018 National Crime Week Victims’ Guide: Crime and Victimization Fact Sheets. https://ovc.ncjrs.gov/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_SexualViolence_508_QC.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2019.